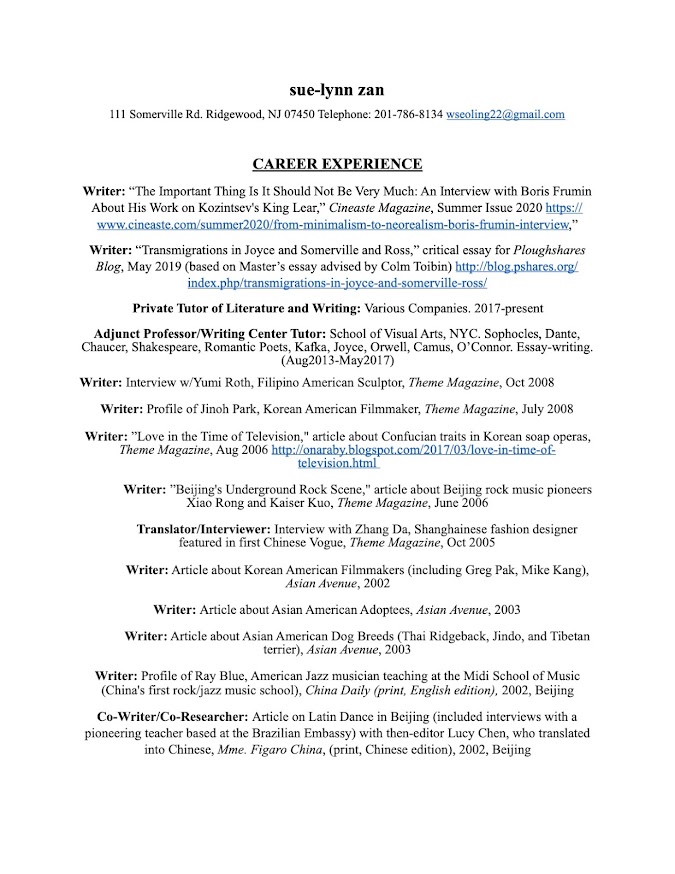

Brigitta Bengyel on Hemingway's "A Moveable Feast," Research Paper/Spring 2017

The Downfall of Zelda Fitzgerald:

An Analysis of Contrasting Evidence

An Analysis of Contrasting Evidence

in A

Moveable Feast

by Ernest Hemingway

by Ernest Hemingway

Brigitta Bengyel

April 9th 2017

Writing & Literature II, School of

Visual Arts

History has seen men take life and drive

out of powerful women countless times. Textbooks teach generation after

generation about the accomplishments of male writers, artists, scientists, and

entrepreneurs. If a field of work is worth writing about, it is more than

likely that the figures written about will be men. Women’s history gets pushed

to the side, or simply not discussed at all. With this trend come the women who

refuse to be erased, the firecracker women who burn down anyone who tries to

hinder them. Zelda Fitzgerald was one of these women. Known to the general

public as the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the shining golden girl of the

1920’s, Zelda’s pure genius and talent are things rarely ever discussed.

Through the eyes of her husband and his friends such as Ernest Hemingway, Zelda

was viewed as a nuisance and a jealous woman out to ruin her husband’s career. The

facts of their lives point in another direction. While F. Scott Fitzgerald and A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

argue that women are behind the downfall of men, a closer look at Zelda

Fitzgerald’s life shows that men are truly the downfall of powerful women.

Zelda Sayre married F. Scott Fitzgerald

on April 20th, 1920 in New York City, and thus began the story of

one of the most chaotic couples in American history (Unknown). Even prior to

the marriage, Zelda was always ready to do what she was not supposed to. In one

of her high school diaries, she wrote “I ride boys’ motorcycles, chew gum,

smoke in public, dance cheek to cheek, drink corn liquor and gin. I was the

first to bob my hair and I sneak out at midnight to swim in the moonlight with

the boys at Catoma Creek and then show up at breakfast as though nothing had

happened” (Talley). At first Zelda refused Scott’s marriage proposal, but then

changed her mind when his first novel, This

Side of Paradise, became successful (Dean). A marriage based on fame from

the beginning was not one that was meant to last. Zelda continuously tried to

work on her own talents such as writing and painting, but was always

overshadowed by her husband and his work. The mere overshadowing was not

enough, as eventually Scott began to plagiarize Zelda’s work and use it as his

own for his novels. In 1922, Zelda was asked to write a review of Scott’s

second novel, The Beautiful and the

Damned. She wrote “I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which

mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage… In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald – I

believe that is how he spells his name – seems to believe that plagiarism

begins at home” (Dean). While the tone was somewhat playful, a trend that would

continue throughout their whole marriage had started. Afterwards, Scott would

steal material from Zelda nonstop. Whether it be obsessively writing down

things she had said or taking her words directly from her writing, the F. Scott

Fitzgerald that is known as a writer would be nothing without his wife. Lawton

Campbell, a friend to the Fitzgeralds, writes:

Zelda was absolutely

essential to him in those days. She was both his inspiration and his anathema.

She gave him spontaneously much of his material and his dialogue. He would hang

on her words and applaud her actions, often repeating them for future

reference, often writing them down as they came from the fountainhead. Zelda

called the tunes, and Scott joyfully paid the piper. Sometimes he had to force

her to leave him alone for a while, so he could concentrate on the material she

had given him and catch up before the next onslaught started. (Cambell)

Eventually Zelda tried to follow her own creative

pursuit in writing, with her first novel Save

Me the Waltz. The book was a fictionalized version of her marriage to

Scott, and this did not please Mr. Fitzgerald. “He

accused her of plagiarism for drawing on their life story – even though he did

the same and had planned to use some of the same source material for his own

novel, Tender Is the Night. He demanded that she revise it.

She did, and it was published in 1932” (Legacy Staff). Despite Zelda giving

Scott almost all of his material, her attempts at being creative were shot down

every time, as their marriage along with Zelda’s confidence and sanity

deteriorated.

In 1924, the Fitzgeralds moved to

Paris where Scott would eventually befriend Ernest Hemingway and become a large

part of Hemingway’s autobiographical “fiction” novel, A Moveable Feast. The novel documents Hemingway’s time in Paris

with his first wife, Hadley, and features many stories about Scott and some not

so pleasant thoughts and comments about Zelda. Upon first meeting Zelda,

Hemingway wrote:

Zelda

had hawk’s eyes and a thin mouth and deep-south manners and accent. Watching

her face you could see her mind leave the table and go to the night’s party and

return with her eyes blank as a cat’s and then pleased, and pleasure would show

along the thin line of her lips and then be gone. Scott was being the good

cheerful host and Zelda looked at him and she smiled happily with her eyes and

her mouth too as he drank the wine. I learned to know that smile well. It meant

she knew Scott would not be able to write. (Hemingway 180)

Throughout A

Moveable Feast, the reader gets the impression that Zelda absolutely wants

to destroy Scott’s career because of her jealousy. Without knowing any other

information about Zelda, this becomes easy to believe. Hemingway’s writing is clear

and convincing, clearly stating, “Zelda was jealous of Scott’s work… He would

start to work and as soon as he was working well Zelda would begin complaining

about how bored she was and get him off on another drunken party” (Hemingway

180). From a man’s perspective this seems valid, but from a general

perspective, both Zelda and Scott were well-known alcoholics (Unknown). Hemingway’s

bias shows through as he clearly favors Scott and wants to show him in a

positive light while speaking lowly of Zelda. In a way, it can be argued that

Hemingway was threatened by Zelda’s caustic personality. Throughout Hemingway’s

adult life, he was always married and went through 4 marriages until his

suicide in 1961. All of his wives were docile, which is how he expected all

women to be (Hines). Zelda being the

complete opposite was bound to get some unfavorable reactions from the

misogynistic writer. Later in his novel, Hemingway states, “Zelda did not

encourage the people who were chasing her and she had nothing to do with them,

she said. But it amused her and it made Scott jealous and he had to go with her

to the places. It destroyed his work, and she was more jealous of his work than

anything” (Hemingway 183). The snide comments towards Zelda continue through

the novel until Hemingway breaks and blatantly lets Scott know his feelings

towards Zelda in the passage:

”Forget

what Zelda said,” I told him. “Zelda is crazy. There’s nothing wrong with you.

Just have confidence and do what the girl wants. Zelda just wants to destroy

you.” “You don’t know anything about Zelda.” (Hemingway 191)

Although the men both want to put an end to Zelda’s

“madness” when it comes to her hindering Scott’s writing, Scott still manages

to stand up for her when another man decides to call her crazy. This reinforces

the idea that Scott needed Zelda more than anything. Under the disguise of

calling her a muse, Scott yearned for Zelda’s writing and material to continue

his own writing and drive his career.

Even

past A Moveable Feast, Hemingway

would not let go of the idea that Zelda was the one ruining Scott. In a letter

to Arthur Mizener, Fitzgerald’s biographer, Hemingway states:

I believe that basically you write for two

people; yourself to try to make it absolutely perfect; or if not that then

wonderful; Then you write for who you love whether she can read or write or not

and whether she is alive or dead. I think Scott in his strange mixed-up Irish

catholic monogamy wrote for Zelda and when he lost all hope in her and she

destroyed his confidence in himself he was through. (Gent)

While the men

continued to go on about how Zelda was the one at fault, Zelda’s mental health

was going downhill fast. Scott’s constant gaslighting and erasure of her

creative endeavors led to multiple mental breakdowns that sent Zelda to various

mental hospitals. In a journal entry, Scott explained a strategy he would use

to stop Zelda from writing more fiction, after their argument over the content

of her first novel. “"Attack

on all grounds. Play (suppress), novel (delay), pictures (suppress), character

(showers), child (detach), schedule (disorient to cause trouble), no typing.

Probable result - new breakdown." (Showalter). The breakdowns simply got worse

through more manipulation, and by the 1930’s, Scott and Zelda parted ways

although they were never officially divorced. Zelda checked into a mental

hospital, while Scott continued to be an alcoholic writer (Curnutt). With enough material to establish himself as

a great American writer, Scott was well-off but was seemingly unable to work

without the presence of his wife. Zelda continued to try to become successful

through writing and painting until her untimely death in a fire at Highland

Hospital in 1948 (Curnutt).

When thinking of powerful women in

American history, and women who refused to be silenced despite all odds, Zelda

Fitzgerald will never be forgotten. Although she was shot down for the entirety

of her marriage with Scott, she never stopped trying to establish her own

career. Through the eyes of others such as Ernest Hemingway, Zelda was merely

another woman in the way of a man’s career. In reality, Zelda was the force

behind Scott’s career. As seen in the quote, “She was a woman who adored and

hated her husband, who adored and oppressed and victimized her” (Beaumont),

both parties can be blamed for who destroyed whom, but evidence goes to show

that their tumultuous marriage brought Scott to fame while bringing Zelda into

madness. Scott’s heartless need for material took a powerful woman with endless

potential and drove it into the ground, leaving the world with a haunting

hidden story of a man taking advantage of woman’s spirit and creativity, along

with falsely accepted ideas of who Zelda Fitzgerald truly was.

Works Cited

Beaumont, Peter. "'Call Me Zelda':

Writers Take on Troubled Life of F Scott Fitzgerald's Muse." The

Observer. Guardian News and Media, 20 Apr. 2013. Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Campbell, C. Lawton. "The

Fitzgeralds Were My Friends." The Fitzgeralds Were My Friends.

N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Curnutt, Kirk. "Zelda Sayre

Fitzgerald." Encyclopedia of Alabama. Troy University Montgomery,

15 Mar. 2007. Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Dean, Michelle. "The Myth of Zelda

Fitzgerald – The Ringer." The Ringer. The Ringer, 27 Jan. 2017.

Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Gent, George. "Hemingway's Letters

Tell of Fitzgerald." The New York Times. The New York Times, 5 Oct.

1972. Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Hines, Nico. "The Perils of Being a

Hemingway Wife." The Daily Beast. The Daily Beast Company, 23 Feb. 2014.

Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Showalter, Elaine. "ZELDA

FITZGERALD." ZELDA FITZGERALD. The Guardian, 12 Dec. 2002. Web. 09

Apr. 2017.

Talley, Heather Laine. "Zelda Wasn't

'Crazy': How What You Don't Know About Fitzgerald Tells Us Something About

'Crazy' Women, Then and Now." The Huffington Post.

TheHuffingtonPost.com, 20 May 2013. Web. 09 Apr. 2017.

Unknown "Zelda Fitzgerald: Beneath

the Glittering Surface." Legacy.com. Legacy.com, 14 Oct. 2016. Web.

09 Apr. 2017.

Comments

Post a Comment