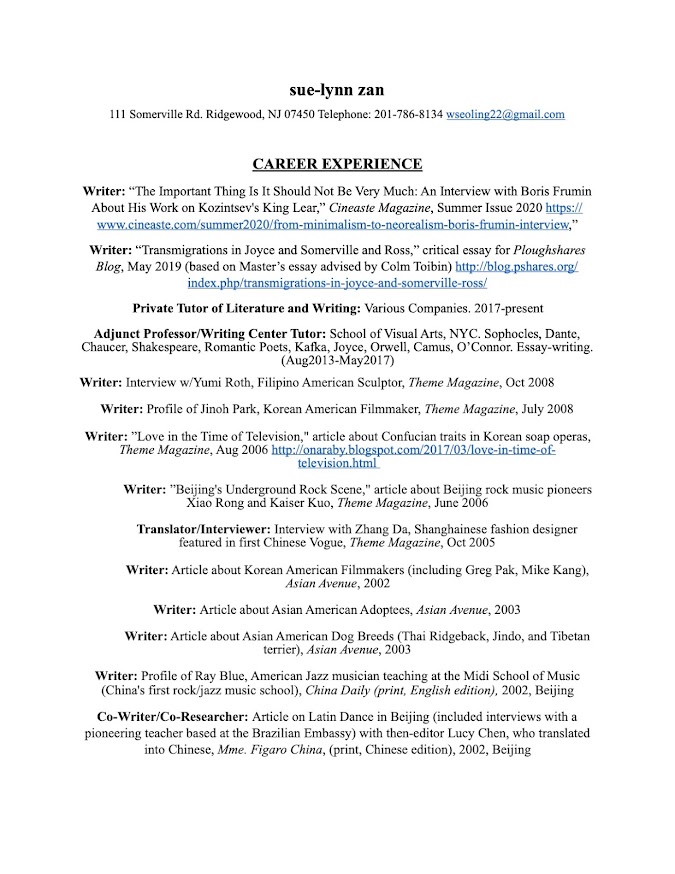

Fay Fan on Sophocles' "Antigone"/Fall 2016

Fay Fan

9/29/2016

Writing and Literature Ⅰ,

School of Visual Arts

“What Were You Thinking?”— Seeing

Through Antigone’s Tragedy

For readers who have not really studied Antigone, it is easy to form a preconceived notion that the title character

plays the role of a hero. From this standpoint, Antigone becomes a song of praise for a woman who fights against a

new despot for the honor of her brother and herself. However, after deeper

rereading and study, subtle disharmonies gradually emerge. The sentences and

words picked by Sophocles point to a conclusion—Antigone, the main character, has

the sickest mind compared to others. Hence, Antigone

is the tragedy of a sad and sick character whose fate is hardly changed by her

tragic flaw, nor is her tragic personality shaped by her miserable experience.

This understanding leads to the principle of tragedies.

Several confusing details and conflicts in the script begin the

story’s excavation. The very first conflict that will be noticed is that

between Antigone and Ismene. As sisters, they share love, emotions, and even values.

However, in their first argument, Antigone’s attitude quickly shifts when

Ismene opposes her, and some harsh words emerge, such as “ill-fated path” (Mulroy

7) or “I’ll despise you even more for silence.”(Mulroy 8) Obviously at this

point, Antigone has viewed herself as a lone hero. A detail which is very difficult

to detect in Antigone’s last words can also serve as evidence. She addresses

the audience and says, “O look at me, rulers of Thebes, the single survivor, the

daughter of kings” (Mulroy 48). Although her sister never dies in the story,

for Antigone, Ismene is no longer a member with a “noble heart” (Mulroy 5) –

this word is usually understood as a “brave heart”, but what if it literally

means “noble” heart? A similar hurtful expression shows again at Ismene’s next

entrance with, “I don’t love friends who offer only words.” “Ask Creon that.

You guard his interests well” (Mulroy 30) and, “Your views seemed fair to some.

To others, mine.” (Mulroy 31) Antigone’s words become mean even though she said

she would love every friend, even though she told Creon, “My nature calls for

sharing love, not hate.”(Mulroy 28) No, she does not love them, actually. Love

is supposed to be a moral value here, not a voice from the deepest part of

Antigone’s heart.

Another suspicious conflict exists in Antigone’s attitude

toward life and death. Every reader knows Antigone treats death as a gift:

Do what you please. I’ll bury him. To die

attempting that seems glorious to me.

Beloved and loving, I’ll lie down with him,

a holy criminal. …

I’ll rest with them forever there (Mulroy 7)

The

same is true when she is talking to Creon:

Moreover, I consider death before my time a gain.

For who with troubles numerous as mine

would not call dying young a benefit?

For me, the pain of suffering such a fate

is nothing. If, however, I allowed

my mother’s son to lie unburied, that

would truly hurt. This

doesn’t hurt at all.(Mulroy 25)

She repeats her claim again and

again until the death sentence is pronounced, and so it makes sense to all.

Antigone is the victim of those horrible events that happened during and after

her father Oedipus’s life. Death seems a relief for her, indeed. Nevertheless,

Antigone sings constantly and almost cries out on her last journey. She sings

for her sorrowful fate, her unfair encounters and hopeless life. Why would a sane

adult do such thing? Here, Antigone violates her previous oath and sings like

she wants to gain sympathy from others – she does, through the response of the Chorus

– and change her fate of death. This is not what a hero in Greek myth would do.

Therefore, Antigone’s behavior is the clue of the truth that she is not a hero

but a person with faults.

If reconsidering this character from a more broad

perspective, the real features of Antigone become apparent. Some aspects of

Antigone can’t be ignored: she is a teenager, she was a princess, and, as Creon

emphasized, she is a female. In ancient Greece, females did not have high

social status. They kept focused on their domestic chores, were blocked from

social and political activities, were regarded as a little bit higher than men’s

slaves. As a female, unavoidably, Antigone is not able to consider things from the

city’s, or, males’ perspectives; hence, she thinks Creon’s decree was issued

for her especially, which is not true, and totally ignores the political meaning

of this law. (Mulroy 5) Besides, after Oedipus was exiled, Antigone’s identity

changed; she is no longer a princess but the daughter of a sinner. When her

brother died, this transition happened so suddenly that she could hardly take

it. Therefore, when her sister Ismene seems to be accepting of this fate,

Antigone feels betrayed; that’s why she thinks herself as the only survivor of

her royal family.

Now think of this situation: a teenage princess, bereft of

her family member, betrayed by her only relatives, transformed into a sinner - to

her, laws and judgment are unfair. At the moment, Antigone has more pain,

hopelessness and anger rather than grief. She is going against her unfair fate by

the only way left, which is death. To Antigone, death is her revenge, her

punishment toward those who are mean to her. This young child was driven crazy

by what she suffered; she believes that she is abandoned even if with public

opinion and the gods’ law on her side. This theory explains this “sick”

statement to a certain extent: “When husbands die, you find another one. You

have another child if one is lost” (Mulroy 46). During her lengthy song before

dying, Antigone’s attitude changes several times. Sometimes she wants to die,

sometimes not. Of course she still hopes to survive. But her life has no possibility

of changing, and to die is the only way to obtain peace and fulfill her last

struggle against the world.

Here, we see a perspective that a tragedy is a tragedy when

the consequences cannot be blamed on someone or something, and the facts cannot

be changed. In Antigone, every person

has his/her reasons, and every person makes his/her mistake(s). The source may

be the oracle of Oedipus, but how can we, especially in ancient Greece, blame a

god? With all of these elements intersecting, events happening, and the rest

meant to happen, audiences can only watch. This forces one to rethink humanity.

This is where the power of tragedy is located.

Comments

Post a Comment